Among Maya Angelou’s Last Words: Praise For An Overlooked Freedom Summer Book

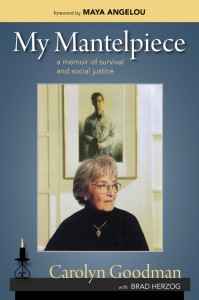

Among Maya Angelou’s last published writings is a tribute to a new, but mostly overlooked, book that sheds valuable context on Mississippi’s Freedom Summer – on its 50th commemoration.

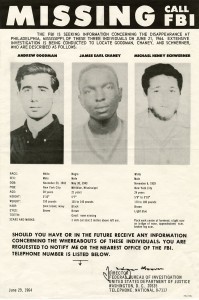

“The murders of Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Mickey Schwerner rocked me to the core of my very being,” wrote Angelou in the foreward to My Mantelpiece, a memoir by Carolyn Goodman, whose son was murdered in Mississippi in 1964 along with his two civil rights co-activists.

“I was used to white men killing black men,” Angelou wrote. But I was not used to white men killing white men. …. And I felt for the mothers of the white boys. You see, the mother of a black boy knows that when he leaves in the morning, she may never see him again. But the white mother didn’t know that.”

men killing black men,” Angelou wrote. But I was not used to white men killing white men. …. And I felt for the mothers of the white boys. You see, the mother of a black boy knows that when he leaves in the morning, she may never see him again. But the white mother didn’t know that.”

While My Mantelpiece is ostensibly a posthumous memoir (ably authored by writer Brad Herzog), it provides valuable context for the times and a revealing look at the psychological, cultural and familial reasons why Goodman’s deadly trip to Mississippi half a century ago was almost decided at birth.

What kind of values, what sort of imperatives to do the right thing, how did a deep family respect for social justice and empathy for the underdog make Andrew’s trip to Mississippi so inevitable?

Those are some of the broad contextual revelations this book brings to all who were deeply affected by the Freedom Summer and those who ponder the questions of what makes some good people do evil and why there are others willing to risk their own lives to fight evil.

The answers to those questions are insights into why Maya Angelou and Carolyn Goodman grew so close.

“Carolyn Goodman and I liked each other very much. We just admired each other. Beyond that, there was affection. But there was admiration, too, because each knew who the other one was. I knew she was a strong and loving woman. And she knew I was the same….So I liked her and loved her.”

I was 15 years old when Goodman and his friends were killed, but the shock of their deaths changed my life and the way I have lived it.

Before their deaths, Freedom Summer was hardly in my thoughts. I was totally absorbed in my own world: more concerned with girls, getting my driver’s license and conducting weird science experiments that eventually propelled me to the International Science Fair and my selection as a Westinghouse (Now Intel) Science Talent Search finalist.

After their deaths, a growing compulsion grew that eventually led me to the social justice gateway drug: attending a march.

Then participation.

Eventually I led one. That got me kicked out of the state.

While my own involvement with the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi is far less than it should have been, my actions were still racial and cultural apostasy. This was especially true for someone like me whose family had played a major part of the power structure for more than a century — including a U.S. Senator who was the first to codify Jim Crow segregation when he wrote the Mississippi constitution of 1890.

I have always wondered why they did it — not just Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner — but all of the Freedom Riders, marchers, demonstrators. Why risk it all for someone you never met?

A sense of decency, moral responsibility, the sense that you are your brother and sisters keeper?

But those are just pat answers. Platitudes. More importantly, where’s the fount of those convictions? What forges them into a personal calling that cannot be denied.

Carolyn Goodman’s memoir answered many of those questions for me.

On the surface, the book follows a socially concerned, middle-class, Jewish family in New York. But deeper truth emerges from such minutiae. Small details gather moral weight and transform themselves into an irresistible force that cannot not be denied, even unto death.

In the hands of a lesser author, those details might be boring. But Herzog writes with a clarity that describes the clear trajectory where each contribution of each small force can be seen in the vitality of the ultimate whole.

Maya Angelou wrote in the foreward that, “People live in direct relation to the heroes and she-roes that they have, always and always….We have to have the people who became famous for what they did. And I think those three are unmitigated heroes, so we have to lift them up and show them to the world.”

If you have even the smallest interest in the Freedom Summer and its consequences, this will add new, never-before-seen context.