Ice Climbing: How To Die. How Not To.

In all my thrillers, I try to make things as authentic and real by personally doing what my characters do — within the realm of ethics, legality and personal ability.

While the act of using a weapon or engaging in particular activities can be demanding, the process makes it easier in the long run to describe how a character would feel and to know what descriptions are accurate.

Obviously, I can’t put everything about every experience into a book, and so in the past, a lot has been left on the cutting room floor as it were.

So, last year I started a site:

Tactical Trekker: Do It Right. Don’t Die.(http://tacticaltrekker.com)

Tactical Trekker includes the out-takes from the activities that get used for book research. I intend to use the lessons and experience from creating and building Wine Industry Insight (http://wineindustryinsight.com) into a profitable digital publication that’s now almost three times larger than the number two premium wine industry online operation.

The following is a post from this morning’s Tactical Trekker. I’ll occasionally cross-post items.

Please let me know what you think of this effort.

Ice Climbing: How To Die. How Not To.

When avalanche conditions turned us back from summiting the 12,300-foot California Matterhorn right before New Years, we snowshoed back down the mountain and went ice climbing up an 80-foot frozen waterfall west of June Lake. The waterfall, like the mountain we had left, was blanketed in fresh powder.

Being new to this, I made all the usual mistakes and floundered up the ice face, especially as I lost one foothold after another before learned the secure how to kick the crampons into the ice face.

But the photo, above, (taken by fellow climber Jeffrey Addison) managed to catch me at an odd moment actually doing something right. My right foot is kicked into the ice and roughly horizontal. But my left foot is slanted up: a newbie error and one that can fatigue calves very quickly on a long climb.

Even though I lost footholds frequently, having four points of attachment to the ice (two axes and two crampons) reassured me, even on those early learning times when both footholds failed. Rule is always have three attachment points at all times. Don’t get in a hurry and try to move more.

Tethers/lanyards are a safety balancing act. In the photo above, my left hand is swinging the ice axe with a lanyard running from the head of the axe and tight to my wrist.

On the one hand, a lanyard can prevent loss of the axe if you drop it. And prevents it from becoming a deadly missile for climbers below. On the other hand tethers can become instruments of self-multilation if they swing wildly during a slip or a fall.

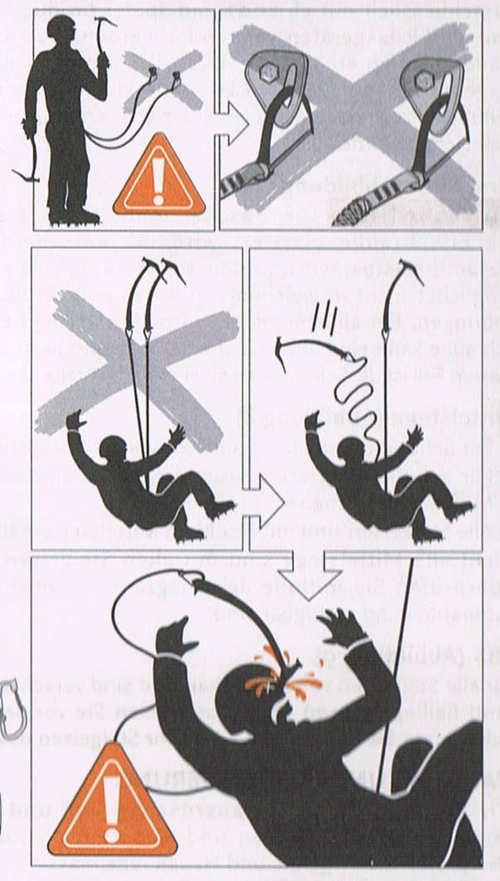

Kudos to Black Diamond Equipment for the graphic illustration above which comes from an equipment brochure.

It leaves little to the imagination about what what could happen if you attach their gear incorrectly. Visualizing this helped me maintain an iron grip on both my ice axes.

Double kudos to California Alpine Guides and its owner, Dave Miller for the great training on the ice and on the mountain.