From Saint To Devil: A Path Carved By Head Injury

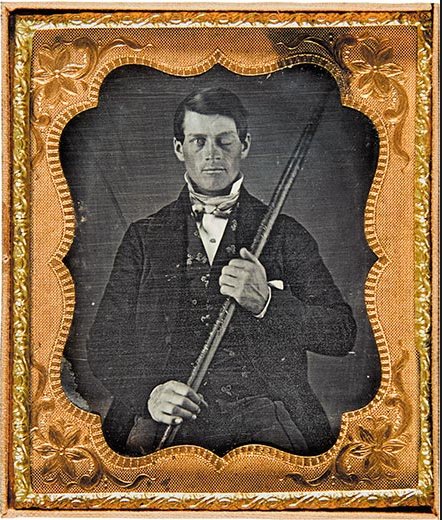

Phineas Gage woke up one day as a saint and went to bed a devil. All thanks to a brain injury.

The following comes from Chapter 32 of my fact-based, investigative thriller, Perfect Killer which deals, among other things, about how the ability to act morally and “do the right thing” can be altered by physical brain injuries and psychopharmacology. And that just because an injury can’t be seen or detected by current scientific methods does not mean it’s not there.

The man being discussed in this scene at the Pentagon — Phineas Gage — is a real man and everything said about him is scientifically verified.

For more about Gage, I would recommend starting with this article from Smithsonian Magazine and then the Wikipedia entry. Your journey from there can be a long, winding and rewarding one. Indeed, it was part of the inspiration for Perfect Killer. That and a secret psychopharmacology project at Walter Reed that aimed to create perfect killers through the magic of brain chemistry.

You can read about that secret project and read the FOIA documents obtained from Walter Reed at PerfectKiller.Com.

In the following chapter, they talk about Gage, his injuries, about the secret psychopharmacology program to engineer perfect killers (Enduring Valor) and, last, about the moral implications of altering free will and doing the right thing — whether by injury or by medication.There is a lot more about that topic in Perfect Killer

AND NOW THE PROMISED CHAPTER FROM PERFECT KILLER INTRODUCING PHINEAS GAGE

“Enduring Valor’s genesis began in the late 1930s when Frank trained as a neurosurgeon. Back then, opening up the cranium led to death as often as not. Like many aspiring physicians interested in the nervous system, Frank learned about Phineas Gage in med school. But unlike most of them, the implications obsessed him.”

“Gage? Who’s that?”

“A twenty-five-year-old railroad construction foreman transformed by an industrial accident in 1848. Gage’s employers, coworkers, friends, and family unanimously praised him as an intelligent, responsible, honest, polite, disciplined—moral—man. Then late one hot summer afternoon in Vermont, Gage made a near-fatal mistake using a four-foot steel pike to tamp explosives into a drilled rock hale. The powder exploded, driving the steel pike into his left cheek, through his eye socket, and the frontal lobes before shooting out the top of his head.

LaHaye sat down and sipped at her cup before continuing.

“After having the steel pike blasted through his head, Phineas Gage recovered, remarkable given the state of medical care at the time. After his recovery, doctors found his intelligence unaffected and no physical incapacitation other than losing his left eye. But the steel pike changed his entire personality. Instead of the former Sunday-school teacher, the physically healed body housed a profane, venal, violent brute with no self-control or sense of responsibility. Call it self-control or free will, Gage had become a victim of his new biological configuration. The ‘bad’ Gage had evicted the ‘good’ Gage.”

She took another sip, then held the saucer and cup in her left hand.

“Gage fascinated Frank Harper, who had treated more than his share of head wounds, so he kept a notebook containing the names and serial numbers of the patients he treated along with fairly precise descriptions of the wounds and treatment. The War Department funded him to follow up on these men, to interview friends, family, and work associates on personalities before the war and after.

“He found many unchanged.” She gazed out the window. “But he also found some startling differences in those who had specific wounds in the frontal lobes. Some had become violent like Gage and wound up in jail.” LaHaye turned back toward Gabriel. “I know of at least two cases where Harper’s notes and medical records and testimony kept men from being executed for murders they committed.

“’Harper’s work prompted the Army to fund a major research effort and essentially gave Harper a recently vacated POW camp in Mississippi. From about 1947 and well into the 1960s, Harper’s people brought in patients for study and sent out teams to prisons and mental hospitals to treat those who were confined and unable to travel.”

“General Braxton was one of these?”

LaHaye nodded. “One of Frank’s biggest successes.”

“Thank God.”

“Absolutely. Anyway, Harper’s biggest successes came after he abandoned the surgical route and began experimenting with psychoactive drugs. Harper structured joint development ventures with private pharmaceutical companies—with some success, I might add.

“At any rate, Harper’s public-private partnership evolved into the operation I now head. Harper’s people and a core of researchers who founded Defense Therapeutics looked at the mechanisms of treating ‘Bad Gage’ injuries, and as they developed new formulas, they realized it might be possible to produce a nondepleting neurotrop which temporarily produces useful combat behavior modifications in warfighters to increase battle efficiency and performance. In addition to the focus and stamina, the ideal nondepleting neurotrop induces the warfighter to surrender a large portion of their free will to the command structure, allowing them to better function in a cohesive fighting unit rather than as an individual.”

Gabriel frowned.

“Imagine the huge time and cost savings,” LaHaye offered. “Instead of weeks and months to create units out of individuals, we can accomplish the same thing pharmaceutically almost overnight and at a tiny fraction of the cost. As long as they’re in the zone, they’re perfect killers.”

Perfect killers. In the zone. Gabriel saw killing zombies in his mind and struggled to keep his horror from showing on his face.

“You talk about the ideal nondepleting neurotrop,” Gabriel said. “That makes it sound like there are a lot of them.”

LaHaye nodded. “There are. We thought we had the perfect one back during the first Gulf War.”

“You mean you actually tested one?”

“Not officially. But just in a few units. We deployed buspirone II in a few units and it worked brilliantly for combat effectiveness.” She hesitated.

“But?”

“Gulf War syndrome. I would think you’d know about that given the writings of your cousin.”

“Rick Gabriel’s a fairly distant cousin,” Gabriel said. “I’ve not read much of his work. Should I?”

“He does strike a lot closer to the truth than I’d prefer.” She paused, then changed the subject. “Anyway, we’ve built on the buspirone work and hit pay dirt.”

“How do you know?”

“We’ve done tests with perfectly adjusted doses and formulations,” she said vaguely. “We’ve had none of the long-term side effects from Iraq, unlike the Gulf War syndrome, which continues to plague us, or the rash of murders and assaults by special ops after returning from Afghanistan.”

Gabriel worked to control the unease squirming in his belly and sensed this was not the time to ask further probing questions because he guessed she had already told him more than she should have.

“Have you been reading about that old murder case down in Mississippi? Talmadge, I believe.”

“Who hasn’t? It’s been a running sore on the national news for months now.”

“Does it have anything to do with your work? Or Harper’s?”

“Not that I know.”

“Right. That’s good enough for me.” Gabriel paused. “But, you know, it’s truly amazing that we as a people and our justice system can look at two men who committed identically horrible crimes and send one to execution and spare the other because there is a physical scar we can see.”

LaHaye frowned. “Maybe, but I fail to see how it matters.”

“Well, it does raise some interesting philosophical implications about right and wrong and free will. The religious views of ‘good’ versus ‘evil’ take on new meanings if good or bad behaviors are controlled not by some sort of extrahuman spiritual realm, but by the physical world of neurons, brain physiology, and neurotransmitter molecules,” Gabriel said. “Perhaps of relevance to your research?”

Her frown deepened as the lines in her face branched into a mask of annoyance.

“Really,” Gabriel persisted. “Seeing the scar, knowing about the wound which turned a ‘good’ person into a ‘bad’ one, motivates us to treat that person differently than another person without the wound. Presumably we do that because we recognize the person with the visible wound has a physical impairment to their free will. So, for one we have treatment, and for the other we have punishment.

“But suppose the punished person actually has a physical wound in the brain we can’t detect—perhaps genetic or from some sort of development problem in the brain,” he continued. How can we tell? Suppose there are physical wounds resulting from DNA damage? Shouldn’t society treat them the same as one who has a scar that can be touched? Do we have to touch the scars to believe? Don’t you see? Your research has great philosophical implications for the military, and society as a whole.”

She shook her head aggressively “It’s not my table.” LaHaye waved her right hand dismissively. “It has no operational significance.”

“Of course you are right.” He nodded sagely. “But that’s precisely the sort of speculation obviously a book author would be interested in.” He smiled as engagingly as he could muster.

Her face brightened. “Of course! It will make for some fascinating reading.”

Gabriel stood up. “Thank you for your time and patience with me dropping in unannounced. I definitely see the beginning of a new book here.”

LaHaye’s face beamed. She stood up and walked him through the reception area to the door. They shook hands. Gabriel opened the door to the corridor, then suddenly stopped and turned back to LaHaye.

“Do you have Frank Harper’s contact information? I think he would be a good place to begin the history.”

“Of course.” LaHaye said pleasantly. Gabriel let the door close as she turned to the chief warrant officer behind the reception desk.

“Jenna, please make General Gabriel a copy of all my contact information for Dr Frank Harper.”