My Tesla Evolution 2: Ion Engine + Atom Smasher = Cosmic Engine

This is the third in a series. See also:

- My Tesla Evolution 1: Coil, Laser, Ion Rocket

- How Nikola Tesla & A Butter Knife Turned Me Into A Rocket Scientist

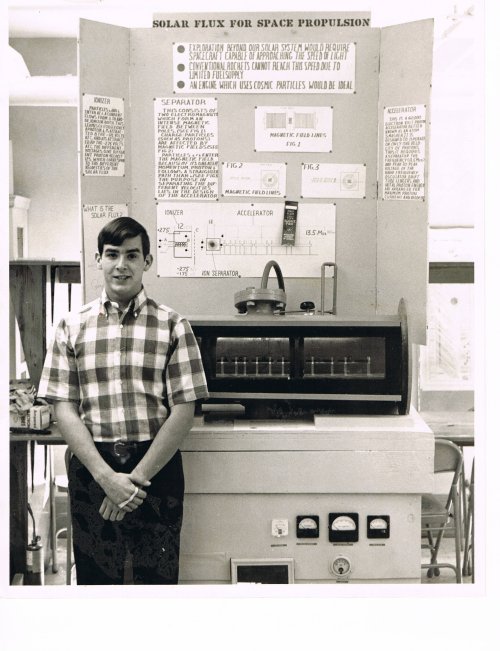

Lewis Perdue The Geek And His Cosmic Engine. The 60 KeV proton accelerator can be seen inside the vacuum chamber. Click image to enlarge and that image to enlarge more.

I never called it a “Cosmic Engine.”

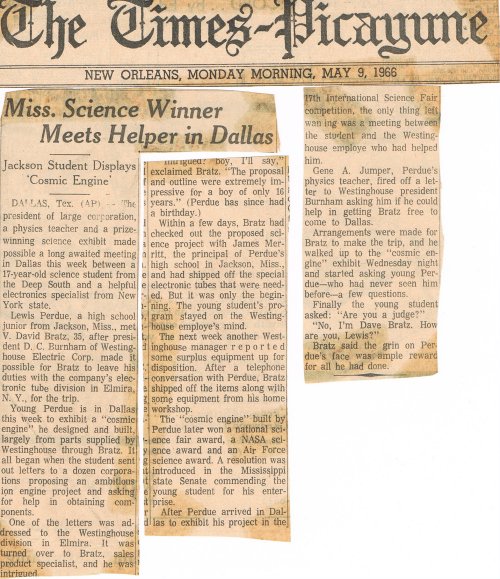

But that’s what the newspapers wound up calling it and the name stuck (see below).

My Papa called it “Project Maybe” and that’s what I liked most. But “cosmic” had a certain ring for the headlines back in the mid-1960s.

And for all you Nikola Tesla fans: note that I got key pieces of equipment from the Westinghouse Corporation. Westinghouse was founded on Tesla’s patents for generating and using alternating current electricity.

No accident. No irony. I knew that before I approached them for help.

At the end of the last post (The Tesla Evolution 1: Coil, Laser, Ion Rocket), I won first prize at the State science fair in 1965 but didn’t make it to the International because I had put too much in the exhibit — both an ion engine and a laser.

But deep-space missions had captured my imagination almost as much as Tesla had.

Hmmm … Tesla, deep-space missions, ion engines … charged particles, high-energy physics, the vacuum of space.

So, I imagined a mission so long that it needed to use the scarce particles in space — the solar flux — for fuel.

GEEK-OUT ALERT! A LITTLE SCIENCE AHEAD

There isn’t much in most part of space. In the unimaginably vast spaces between stars, planets, comets and meteors (and the occasional man-made objects and debris) there’s a lot of nothing. The vacuum out there is almost perfect.

On average, there are 5 or 6 particles in a cubic centimeter of space (something the size of a sugar cube) in the neighborhood of Earth. Less the farther you get from a star like the sun.

Those are mostly protons (hydrogen nuclei stripped of electrons). There will also be alpha particles (a helium nucleus…two protons, two neutrons). Those small bits of something filling the nothing consists of a plasma: a mixture of particles with so much energy that the nuclei of matter can’t hold on to any electrons.

And I imagined that people would want to get wherever that was as fast as possible.

So, I thought, maybe you could use a sort of magnetic to gather those particles and concentrate them.And then feed them into something that would go really, really, really fast: a particle accelerator (aka atom smasher).

FIRST, A VACUUM CHAMBER TO SIMULATE SPACE

First I needed to build a vacuum chamber that could approach the vacuum of space. No easy task.

The quality of a vacuum is measured in torr. Atmospheric pressure on Earth (no vacuum) is 760 torr.

Depending on where you are in outer space, the vacuum is 1/1,000,000 (a micro-torr) to 1/1,000,000,000,000,000 torr.

At the minimum, I had to build a vacuum chamber big enough to hold my entire science fair project at a vacuum of at least 1 micro-torr.

In the end, I managed ten times better than that.

Next, I needed to make something that simulated the solar flux. As it turned out, the ion engine I had built the previous year generated just those kinds of particles. This is what gave me the idea for using the solar flux for fuel.

Okay. Vacuum chamber, check. Ion engine/solar flux, check.

THEN, THE ATOM SMASHER

Why a particle accelerator? Because, heoretically, in the vacuum of space, a craft could eventually approach the velocity of the particles from the engine. In the case of a linear accelerator, those are close to the speed of light…so-called “relativistic” speeds.

Of course, there was no way my protons were going relativistic within the tabletop confines of a science fair exhibit. So I settled for demonstrating that the concept was possible and built a 60-KeV accelerator … translated, that’s a 60,000-electron-volt accelerator.

ZAP! That’s one helluva Tesla fix!

If you want to know a little about how I built it, scroll down to the very bottom of this post.

THE EXPLODING TRANSFORMER AND MY BRUSH WITH THE FCC

The juice behind the accelerator was a radio transmitter (oscillator) powered by a 1,000-watt power supply and putting out about 450 watts of radio frequency waves at 13.5 Megahertz. If you uber-embiggen the image of me and the machine, you’ll see that written as Mcs … back then the standard unit of frequency was still “megacycles per second.”

Anyway, the transmitter and its frequency had several unintended consequences.

First of all, in order to get enough current — 200 amps — to the power supply, I had to basically use all of the power coming into the house. So, I took it upon myself to install a switch that diverted all of the electricity coming into the house so it fed into the power supply. The accelerator took most of that power while the rest of the electricity ran the vacuum pumps and other devices.

This seemed to work just fine except that when the accelerator was on, nobody else in the whole house could use anything electrical.

FIRE IN THE HOLE, EXPLOSION ON THE POLE

After I fired up the accelerator the first few times I did it for short periods of time so that the rest of the family could live in the electrical age.

But one Saturday, everybody was away. So I paid no attention to the time.

Then everything happened at once:

The insulation in one of the power supply components (the bleeder resistor) blew, shorted the whole thing out and exploded. The mercury vapor tubes glowed cherry red and the whole power supply the size of a dishwasher with a 150-pound transformer, danced a crazy jig and buzzed like the Apocalypse.

I ran. I played football those days and was in damn good shape. So I didn’t bother to open the door. I ran through the door into the carport just in time to see flames coming out of the electrical transformer on the pole outside the house.

The transmitter power supply short was so powerful and so fast that it fused (melted the insides) of the house main breaker. The short then hit the transformer. Its own circuit breaker should have prevented damage, but must have malfunctioned.

After some house repairs, the replacement of and improved insulation for the bleeder resistor and an additional circuit breaker for Project Maybe, I got back to work.

THE VISIT FROM THE FCC

A van with antennae on its roof arrived a couple of weeks later. The men inside were from the Federal Communications Commission.

My transmitter/oscillator was screwing up WLBT, Channel 3 – one of the two television stations serving Jackson at that time.

Remember that the particle accelerator operated at 13.5 Megahertz. And there were commercial radio stations operating with about half my output.

The nature of a radio frequency transmitter is such that it also generates harmonics — waves that are multiples of the main frequency. These are lower in strength and can be prevented with better engineering than I had managed so far.

My 13.5 Megahertz transmitter was also broadcasting at 27 Mhz and 54 MHz. Channel 3 operated at 54 MHz.

We never knew about the interference because nobody could watch TV at our house when the accelerator was running.

With information from FCC engineers, I re-built the transmitter, solved that problem and got on to creating more and better problems and finally got the whole thing to the International Science Fair.

Another short piece about the cosmic engine and the international science fair. Click to enlarge, then click that image to make it even bigger.

BUILDING A PARTICLE ACCELERATOR IN YOUR GARAGE – THE SIMPLIFIED VERSION

Not to go too far into the fine points of building a linear accelerator, suffice it to say that I needed a series of increasingly longer copper tubes hooked up like an antenna to a radio frequency oscillator. Oscillator meaning that radio wave would go from positive to negative at a very strictly controlled frequency.

The tubes needed to be a precise length, in a straight line and be separated by a very precise gap between tubes. The first tube would attract the positively charged hydrogen nucleus (a proton) and accelerate it into the tube.

Inside the tube the radio wave voltage has no effect. But the frequency is timed so that when a proton exits the first tube the voltage turns positive (shoving the proton along) and the second tube is negative, pulling it along.

So, a shove and a pull in the gap, accelerates the proton faster into the second tube. And that tube has to be longer, precisely longer so that the proton enters the next gap at the exact moment to get another shove/pull and into the next tube.

At age 15 when I started this, I had needed to teach myself calculus since it wasn’t offered in school. However, I had not advanced far enough to get the math right for the tube lengths. For that, I had some help from a staff member at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

With their corrections to my calculations, I built the accelerator.